As it happens my own reverence for water has always taken the form of this constant meditation upon where the water is, of an obsessive interest not in the politics of water but in the waterworks themselves, in the movement of water through aqueducts and siphons and pumps and forebays and afterbays and weirs and drains, in plumbing on the grand scale.

- Joan Didion, Holy Water, The White Album

NOT A CORNFIELD

In 2005, artist Lauren Bon drove a rented water truck onto the concrete bed of the Los Angeles River. She had made this trip many times before, filling up the tank by unfurling the truck’s hose into the river’s low-flow channel, the ten-foot wide trench running between the concrete-encased river banks.

The water that pumped into Bon’s four-thousand gallon truck was mainly wastewater from upstream treatment plants and runoff from LA’s storm drains. Instead of flowing out to sea, the captured water would irrigate one million kernels of corn, sown on a thirty-two acre polluted and abandoned former train yard near Chinatown. Corn is symbolic of course, but it is also very effective at phytoremediation, a process that uses plants to pull contaminants from the soil.1 This plot of land was sorely in need of intervention.

On this particular trip though, Lauren was intercepted by a member of the US Army Corps of Engineers. She explained her project, that this water would be used to rehabilitate the soil of a brownfield site, but the engineer was unmoved. The Army Corps of Engineers is responsible for that stretch of river, and the only entity legally allowed to take water from the Los Angeles River is the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power. Lauren wasn’t allowed to be there, and she certainly wasn’t allowed to take that water.

Not a Cornfield, as the remediative environmental art project was called, succeeded in cleaning the brownfield site which had been acquired by the California State Park System a few years prior. The installation brought life - and visitors - to the previously abandoned plot, the present-day site of the Los Angeles State Historic Park, which officially opened in 2017.

Geologically, the LA State Historic Park, set in the basin flanked by the Santa Monica, Santa Susana, and San Gabriel Mountains, is part of the LA River’s historic floodplain. Before urbanization, during the wet season the unbridled river would overflow its banks and soak the land, recharging the groundwater and adding rich sediment to the soil. However, since the late 1930’s, when the river was concretized to prevent floods, all the rain water that falls on the city’s streets moves through the storm drains and sewer system into the LA River, and then flows out to sea.

Lauren wasn’t allowed to convey any of that wastewater herself, but what if there was a way to divert the flow instead? This guiding question planted the seed for Bending the River.

CALIFORNIA WATER RIGHTS

No one owns California’s water. You’re only granted the right to use it, and to use it for a beneficial purpose. Water is a precious commodity in the state, and that scarcity led to a set of complex rules governing who does and does not have access.

Riparian rights, based on the English common-law system, grant landowners the right to use the surface water on and adjacent to their property and the groundwater beneath it. In the eastern United States, where water is plentiful, simple riparian rights were enough to fairly govern water use.

California recognizes riparian rights, but also established what are known as appropriative rights, which allow water to be diverted from one designated spot for use in another. Appropriative rights developed during the California Gold Rush, when access to water could determine the success or failure of your claim. Prospectors initially panned for gold in rivers or streams, or diverted the flowing water to sluices which would capture the gold for them. Later, they turned to hydraulic mining methods, using a jet of water to chip away dirt and debris, or a rocker box to wash away sediment leaving the gold behind.2

Settlements in gold-rich areas grew rapidly - California’s population almost quadrupled, from 92,597 people in 1850 to 379,994 in 1860.3 Boomtowns needed water to thrive, as did the agricultural land producing food for the new arrivals. As the settlers needed more and more water, conflicts - often violent - quickly arose.

To diffuse these conflicts, the principle of “first in time, first in right” was unofficially adopted, then officially became law in 1855. The first person to take water from a water source, often posting notice of their use on a nearby tree, was then entitled to use water from that location, in perpetuity.4

This “first in time, first in right” system created a concept of water seniority in a state where water is often scarce. Any granted right to water is superseded by any and all previous rights. Your water right only entitles you to water that’s available once every previously-granted right has been fulfilled.

With California’s limited water resources, however, this system proved unsustainable and the state Water Commission - the precursor to the California State Water Resources Control Board we have today - was established in 1914 to govern who had rights to move and use water in the state.

The Water Commission developed a permitting system for granting any new appropriative water rights, and they decide what can be determined “reasonable” and “beneficial” use, now conditions for any water right granted in California. Today, permits even specify the place of diversion, the amount of water that can be used, and the location and purpose of use.

In addition to riparian and appropriative water rights however, California also honors pueblo rights. Superseding all other water rights, pueblo rights were signed into law when California became a state in 1850. This granted existing Spanish and Mexican pueblo settlements control of all water within their city limits. These were the first water rights officially granted by the state, and are therefore “first in time” with seniority over all other California water rights. While they have faced numerous legal challenges, pueblo rights have consistently been upheld by the courts.

This designation, however, created its own set of problems. Los Angeles is a vast and sprawling metropolis - and much of that has to do with water. Los Angeles has pueblo rights to all the water of the Los Angeles River, in addition to having groundwater rights to the vast aquifers underlying the city. In order to access that water, smaller cities and municipalities petitioned for inclusion in the City of Los Angeles. Because of this, the population ballooned, but so then did the expanding city’s need for water, outpacing supply. Los Angeles had a problem.

PAYAHUUNADÜ, ‘THE LAND OF FLOWING WATER’

The “first in time, first in right” doctrine had one glaring omission - California’s indigenous population.

The Owens Valley, the deepest valley in the Continental United States, sits between the Sierra Nevada and Inyo-White Mountains near the California-Nevada border. The Owens River winds through the valley to Owens Lake, the final destination of this 2,600-square-mile watershed. Known as Payahuunadü, this is the tribal home of the Nüümü, the Owens Valley Paiute people.

The Sierra Nevadas cast a rain shadow over the valley limiting precipitation5 but creeks and streams carried the abundant snow melt down from the surrounding mountains, and the Paiute developed unique canal systems to irrigate the land and grow food in a form of proto-agriculture. Under their careful stewardship, the land was fertile6 but their ingenuity also made the land a target - in the 1800s, settlers and ranchers moved in and laid claim to the land, effectively privatizing what the Paiute had once held in common. When the rapidly-growing City of Los Angeles needed water, this is where they turned.

On July 29th, 1905, the Los Angeles Times announced that Fred Eaton, former Mayor of Los Angeles, had purchased “50,000 acres of water bearing land” in the Owens Valley, just upstream from Owens Lake. He then sold that land - and its water - back to the City of Los Angeles. William Mullholland, the famed engineer and superintendent of the Los Angeles Water Department, constructed a 200 mile aqueduct that diverted water from the Owens River before it reached Owens Lake. By 1926, Owens Lake - and Payahuunadü - was dry and Los Angeles was thriving, on appropriated water.

Ten years ago, for the 100th anniversary of the opening of the LA Aqueduct, Lauren Bon and Metabolic Studio made a one-month trek from the Owens Valley to LA titled 100 Mules Walking the LA Aqueduct. This mule march was not to commemorate or celebrate the aqueduct - it was to raise Angelenos’ awareness about the source of their city's water. This survey of the 240 miles of infrastructure that moves water from the Owens Valley to LA is an integral part of the story of Bending the River.

BENDING THE RIVER

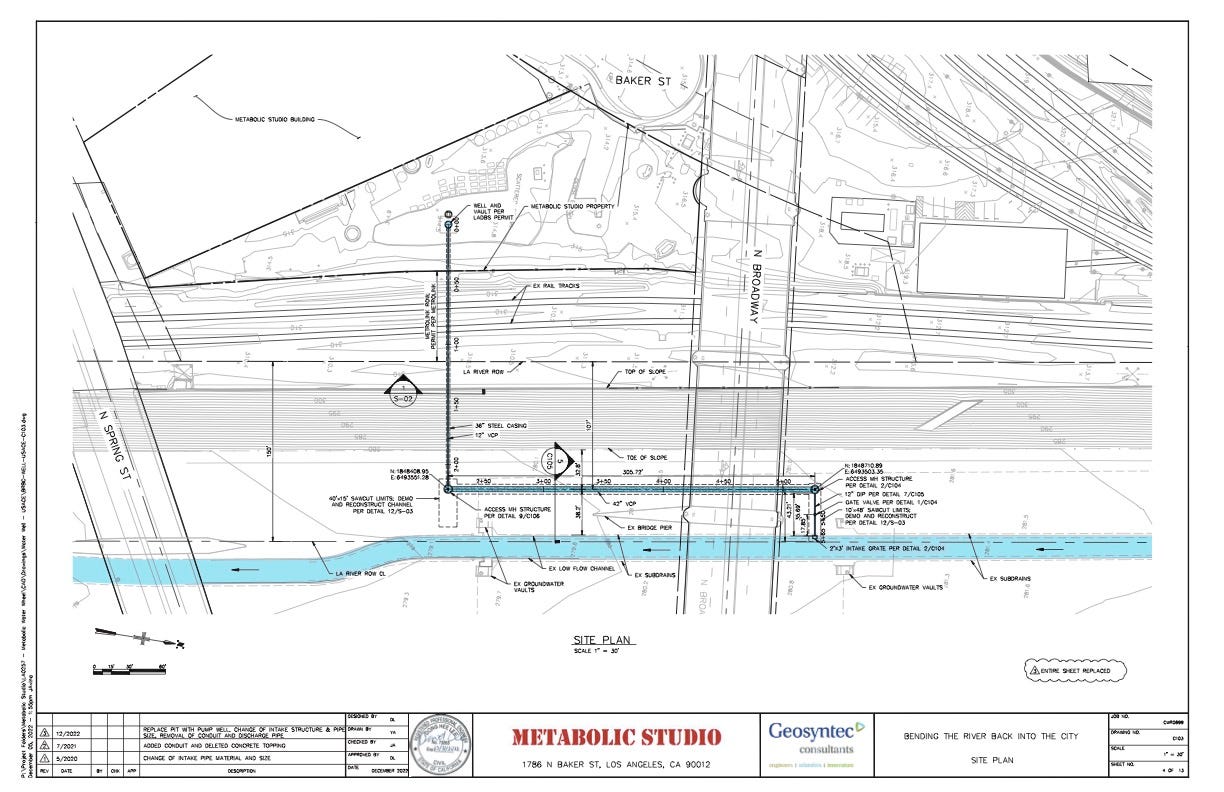

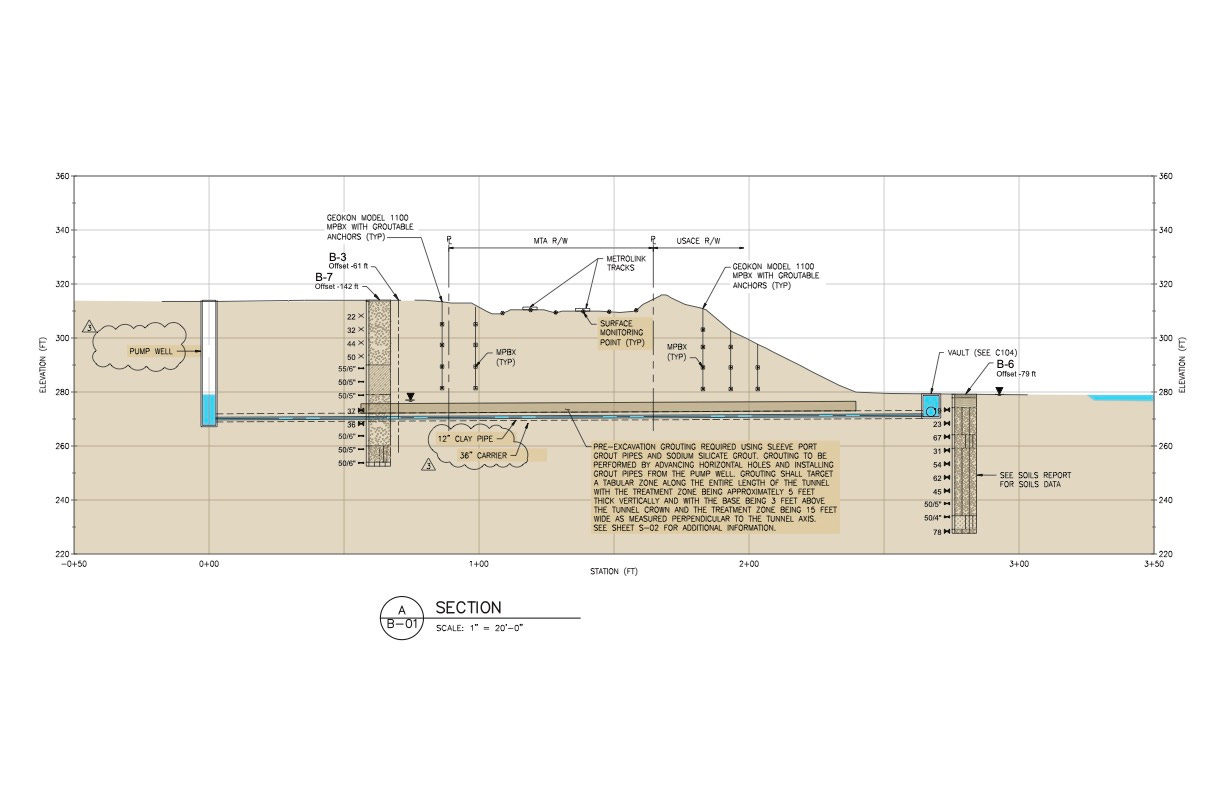

The Los Angeles River was paved to protect the city from flooding, but not a lot of thought was given to the water itself. Bending the River, the first adaptive reuse of the LA River infrastructure, aims to change that. The work redirects a portion of the Los Angeles River to Metabolic Studio for treatment, and then on to the Los Angeles State Historic Park for irrigation purposes, challenging perceived wisdom about the value of the water in the river.

Legal access to this water was Bending the River’s “fatal flaw” objective - without that access, there was no project. The concrete path of the river had been essentially unchanged for eighty years, so there was no blueprint for how to proceed. The essential question then was: “where do we start?”

First, we identified our ideal site, adjacent to Metabolic Studio, just downstream from the Arroyo Seco Confluence with the LA River. With that site in mind, we broke our needs for the project down to three separate requirements:

the right to access the LA River;

the right to use the river-adjacent property;

the right to use the river water itself.

THE RIGHT TO ACCESS THE RIVER

The only two entities with a “Right of Entry” permit for the Los Angeles River are the US Army Corps of Engineers - the federal agency responsible for Flood Risk Management projects - and the Los Angeles County Flood Control District.

We started by approaching the Flood Control District, but they threw us a curveball; while they had the right to access the river, they didn’t own the underlying land. It belonged to the City of Los Angeles. Because the City owned the land, our project needed approval from the City.

We tried to track down the City department overseeing the river land and ended up at the LA City Department of General Services, whose real estate division handles all City property not owned by a proprietary department. Their day-to-day concerns are tangibles like supplies and procurement, and City building and vehicle maintenance. They had no idea what we were talking about and weren’t interested in looking outside their purview to help an untested plan come to fruition. We had to find another way in.

Our third approach targeted the United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE). The concretized LA River is primarily a flood control measure. Because of that, it is considered a USACE Civil Works project and falls under the jurisdiction of the Army Corps. To alter a Civil Works project, you need a Section 408 permit.7 Unfortunately, the Army Corps does not allow private entities to operate in the LA River - or any of their other projects - and Section 408 permits are traditionally only granted to other governmental agencies.

If we wanted to try to get one anyway, we needed a Right of Entry permit for the LA River. Because the USACE doesn’t allow private entities Right of Entry permits, no permits were even a matter of public record. We couldn’t find an old Right of Entry permit and use it as a blueprint on how to make the most persuasive approach.

Even if we could get that Right of Entry permit, we still had a “chicken or egg” problem. The Army Corps wouldn’t give approval for a project in the LA River unless an agreement was in place with the City to operate and maintain the project. The City wouldn’t put an agreement in place to operate and maintain a project if there wasn’t already project approval from the Army Corps of Engineers.

An archival search finally unearthed a Right of Entry permit granted to the Army Corps in the 1940s. To get the permit, the Army Corps first got a recommendation from the City’s Bureau of Engineering, then the USACE took that recommendation to the Board of Public Works, who manage the Department of Public Works. The Board was the granting body for the permit. We finally knew who to talk to next.

The highest-ranking architect in the City of Los Angeles is Deborah Weintraub, the Chief Deputy City Engineer and Architect at the City of Los Angeles Bureau of Engineering. We showed her the Right of Entry permit we’d found, and she agreed with our assessment - if the Board of Public Works approved our project, they could give us the permit we needed. She even agreed to give us a recommendation. We found a chink in the burocreatic armor. We were finally underway.

THE RIGHT TO USE THE RIVER-ADJACENT LAND

The Metabolic Studio building is located north of Chinatown, between Broadway Avenue and Spring Street, on the west side of the LA River. The property line ended a few feet north of the building, bordering an acre-sized parcel owned by LA Metro. That Metro property was essential to the project, for construction and river access, and to secure a path for the water to travel from the LA River to the LA State Historic Park

We decided to ask LA Metro for a fifty-year lease. That felt like enough time to establish the project, from construction through to diverting the water to the LASHP, and then to establishing the benefit to the community. When the LA Metro representative heard our pitch, he took our proposal one step farther and asked if we’d ever thought about acquiring the property outright. Since the property was beside Midway Yard, a large Metro maintenance facility, we hadn’t even considered they’d be willing to entertain the idea but we jumped at the chance.

Selling surplus government land is no easy proposition - it’s carefully regulated. First the property has to be offered to the School District, then to the Housing Agency, and only after they decline can it be offered to the public. Jumping through all the required hoops would delay us, but purchasing the land outright ensured the viability of the project, and would reduce the number of future approvals we would need to secure. The delay would be worth it - once we owned the land, we could move quickly. It took another eighteen months to purchase the property, but once the purchase was completed, another essential hurdle had been cleared.

THE RIGHT TO USE THE WATER ITSELF

While we had cleared two big hurdles, the last one was the biggest; convincing the LA Department of Water and Power to grant us the right to use the water at all.

The LADWP is the largest municipal utility in the United States. It was founded as the Bureau of Water Works and Supply when the City purchased the privately-held Los Angeles Water Company in 1902. Since that time, the DWP has zealously asserted its pueblo rights to the Los Angeles River, as outlined in the City Charter, and its exclusive authority to supply water within the jurisdiction of the City of Los Angeles.

Bending the River would divert the water from the LA River to irrigate the LA State Historic Park and two other potential sites - the Downey Recreation Center and nearby, the former site of Albion Dairy, then slated to become a future park and neighbor to the Downey Rec Center.

With plans in hand - but no agreements in place - we approached the DWP. We wanted to purchase eighty acre feet of water from the Los Angeles River. An acre foot is one football field covered in water a foot deep, and supplies approximately two households with their water for the year. Eighty acre feet would be needed to irrigate the LA State Historic Park for a year.

But the DWP didn’t want to sell us the water. Not because they opposed the idea in principle but because, once again, it had never been done. They had an established rate for recycled water, but the LA River is urban-runoff as well as recycled water released from upstream treatment plants, so they couldn’t offer the recycled water rate. Since the water wasn’t otherwise usable (Bending the River would need to specially treat the water in order to use it to irrigate LA State Historic Park) the DWP didn’t want to negotiate a special one-off rate. They were, however, willing to look the other way if we simply took the water on a “don’t ask, don’t tell” basis.

A handshake agreement wasn’t good enough for a project with a projected fifty-year lifespan. We were negotiating to provide a basic service to the California State Park system. Bending the River may be an art project but the agreement would be binding, and we would have to deliver the water we promised - the park would be depending on it.

The DWP had no objection to the water being used to irrigate the State Park - they just didn’t want to be stuck in the middle. They suggested we seek a water right permit from the State Water Resources Control Board. While this may have been recommended in good faith, it was also a Herculean task and challenged conventional wisdom about water rights on the LA River - especially since the pueblo rights of Los Angeles have long been recognized.

The Water Resources Control Board allocates appropriative water rights, and since the board’s founding in 1914, the Board has never granted a private right to LA River water. Once again, we were pursuing a “first.”

But this was the DWPs recommendation and we proceeded with our application. It was a rigorous process with a long list of requirements and paperwork to file, including extensive engineering and surveying work. Looking forward, we increased our ask to 106 acre feet of water per year in case we were in fact able to add the Albion Dairy and Downey Recreation Center to our plans. The Water Resources Control Board was initially curious what the DWP thought of the application, but since we were able to say the DWP suggested we apply in the first place, the Board was happy to follow their lead.

As we were moving forward with our application, we were also celebrating the election of Mayor Eric Garcetti. Because of his commitment to environmental issues, Garcetti was an early supporter of Bending the River and even signed a letter pledging the City’s support for our water right permit. When the Water Resources Control Board opened the public comment period on our water right application, there was no opposition. The water right permit was formally approved by the state board on May 7, 2014.

Nearly ten years have passed since Water Right Permit #21342 was issued. October 2023 marks the completion of the in-river portion of the project, and during construction this past summer, we brought almost one thousand people down into the river to tour the site. There are always very important questions and conversations that come up. This essay has been written, in part, to answer one of those essential questions - how we got the permit – and we hope this helps people understand the process. We believe that more transparency will set the stage for the future, and create space for more interventions like Bending the River.